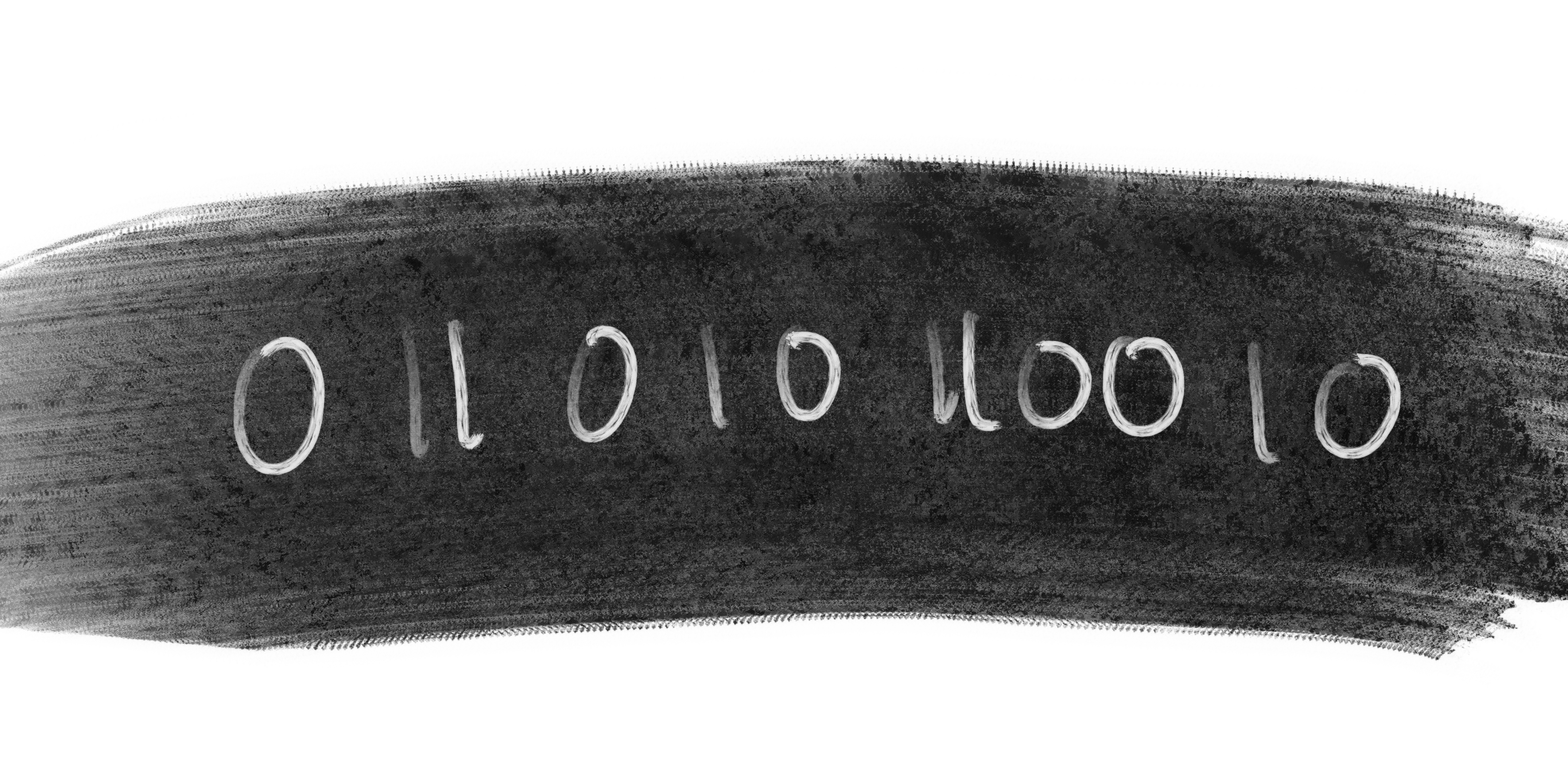

One of the most important things I’ve ever learned was an elementary understanding of computer programming. It’s fascinating really, but amazingly simple when broken down to its key ideology.

My understanding all started when a friend of mine was going back to school and wanted to study computer science and philosophy… At that time, it seemed like those two things were like oil and water. Of course, I laughed for a second and then questioned how the heck he intended on combining the two and he responded with one word: “logic”.

The idea of logic was something I never really dove into understanding, but this conversation was about to be forever enlightening. He explained that everything in computer science could logically be explained as a series of complex “if / then” statements, and then connected that thinking to code. “If mouse clicks here, then open application.”

It was an interesting connection that distills the idea of logic into the most basic understanding and allows it to be applied to anything – even creativity.

Logic, code, and equations are not really part of a creative or design curriculum, and that’s totally fair. It sounds a lot like “thinking inside the box” which traditionally we’ve been allowed to think is the wrong thing to do. However, design isn’t creating something beautiful or emotional; it’s about solving a problem. In order to truly solve that problem, it requires finding all of the “ifs” that go into it, and responding appropriately with a “then”.

Understanding the “ifs” requires a few things. First is empathy. You need to have an idea of what someone else’s root problem is, who their audience is, etc. This may be contrary to your feelings or your opinion, but being able to play devil’s advocate and put yourself into someone else’s position is extremely important in design.

Part of collecting those “ifs” is devising a good creative brief and important dialog between creative and client. The days of “just give me an idea” or “make it look cool” only exist in desperation. Those kinds of projects set you up for failure because you haven’t given your creative team a problem to solve and can always reply with the subjective answer: “Nah, I don’t like that”.

A good brief and good dialog help mitigate errors in subjectivity and allow a design to be “right” instead of just “good” or “bad”.

Taste and subjectivity are commonly looked at when thinking about designers and creatives. It only takes a basic understanding of design fundamentals to make something aesthetically pleasing, but that’s only half the battle. If one makes a beautifully simple, clean, modern space for a client who prefers bold, colorful, expressions, then the aesthetic falls apart in solving a problem and answering a brief. It’s important to put your own opinions and subjectivity aside in order to do so. Ultimately, your client is paying for your final product, and your job isn’t to educate them on taste.

That’s where things can sometimes get difficult. A lot of designers have a good sense of taste but it often becomes a crutch. Even things as simple as client opinions are input to your problem. “If my client loves red, then I need to introduce red into the design”. These are also the most difficult and mundane “ifs” to attain. That’s where collaboration, incremental shares, and open dialog come in to ensure your design isn’t spoiled by an aesthetic appreciation that you and your client may not share.

Ultimately, beautiful isn’t always the goal when it comes to design. A screwdriver will never be beautiful, however, it was intelligently designed to solve a problem. Designers should have a strong opinion of aesthetic and that can come forward in their personal brand, company brand, fine arts, etc., however when solving a client’s problem, the goal should be to find the “right” solution, and not necessarily the one you may like the most.